“I must warn you that I’m going to be speaking about death in no uncertain terms here. Mortality. Muscles, organs, nerves, blood, viscera. Fat. Things of the flesh. Of what we are made of. Of where we’re all heading. Of the dignity we might all wish for our cadavers. Morbid? Maybe. I want to speak of the dead body. How human remains have meant certain things in certain times for certain reasons. I want us to think together. Imagine some of the ways in which the dead have taught the living across centuries. This theatre, tonight, will be the theatre of our bodies.”

When I’m creating a work, the world suddenly seems imbued with clues and connections. Ideas suddenly seem to spring up that connect with and illuminate the line of research; whilst research in turn uncovers previously unconnected associations. Then, suddenly there’s a criss-crossing of themes and associations. This enables me to create a dramaturgical logic that can move across time and place.

My project began with reading Jonathan Sawday’s The Body Emblazoned. This book totally fascinated me and I decided to create a work on anatomy theatres. As I was developing my thinking for this, I began to reflect on death and mortality. I wanted a strong musical element and decided that the musical saw would be a great sound as well as a pun on cutting and the use of saw in surgery and anatomy historically. I invited David Coulter to create the music. I then hit on the Mahler and my passion for Das Lied von Der Erde (Song of The Earth). The Mahler story in the piece deals with personal memory, that then began to intersect with other ideas emerging in my research. I fell in love with this piece of music since encountering it in a Kenneth Macmillan ballet of the same title Song of the Earth when training at the Royal Ballet in the 1960s. This fact had subsequently collided with my relationship with my own mother. She had concealed our Jewish identity until I was in my 30s, due to post-WW2 trauma and anxiety about anti-Semitism that she was certain would arise again. She defended her secret to us by stating that she wanted us to live without fear. And that if we didn’t identify, presumably we would be safe. When discussing her funeral with her the year before she died, our mutual revelation that we both wanted this Mahler music at our own funeral was a poignant moment of truth. Because, in sharing our respective love for this work – composed to ancient Chinese poems but in fact a Kaddish (Jewish prayer for the dead), composed feverishly by Mahler during a time of enormous heartache and grief – we were finally acknowledging our German Jewish heritage. I played the piece as her coffin was brought in. Another twist to these themes: that the expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka’s jealous passion about Alma Mahler, the much-loved widow of the composer Gustav, drove him to his extraordinarily fetishist act of commissioning a life-size doll, led to another intersection of ideas: Kokoschka beheaded his Alma doll in a weird public ritual. This act of symbolic annihilation presented the topic of decapitation, that in turn relate to both the Medusa myth and the guillotine (see below). Then, the latter connects to the wax works of Marie Tussaud whose first commission from the Revolutionary leaders was the decapitated heads of the Royal Family (whom she had known as a young art tutor at the palace of Versailles). The 18th century use of wax as a medium for representing human flesh lead me to understand those anatomical figures perfected in Italian workshops, that include the extraordinary Anatomical Venus of Clemente Susini. Wax, in turn conducted me to Descartes and his famous meditation on the verification of truth through doubt in his discussion of the senses in relation to a wax candle. That wax melts was key to his theory elaborated in his ‘Second Meditation’ (Discourse on Method and The Meditations. pp.108 -109). Vital to thinkers of this time was certainty, as this lent authority and the assurance of power and control over the world both material and of ideas. Descartes, developing his famous theory of doubt as a path to truth, was a man of his time.

THE BODY IS A BOOK

“If the body is a book, it’s certainly the most extraordinarily beautiful, perfect, breathtaking volume”

The idea of the body as a book goes back centuries. During the Renaissance, a time of European invention and colonisation, various metaphors came into use to describe the astonishing – and public – voyages of discovery into human flesh itself. The body was compared to a landscape or territory that could be taken possession of and mapped, and, vitally, as a text that could be read and interpreted. During the Enlightenment in Italy, La Specola (Observatory) Museum in Florence, home today to the works of the brilliant wax anatomist Clemente Susini (1754 – 1814), the idea of the body as book was extended in the actual organisation of the museum: the body is presented as an Encylopaedia. On the walls are many detailed anatomical drawings with reference numbers that connect to materials that can be handled in cabinets below; entry upon entry, getting deeper and deeper inside the body’s parts.

In the 19th century, probably the most famous illustrated anatomy textbook of all times, Gray’s Anatomy (41st edition edited by Standring, Susan. 2015. New York: Elsevier), first published in 1858, was not the first publication to illustrate the human body in line drawings. The pioneer of such in Europe was Andreas Vesalius, whose revolutionary De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On The Fabric of the Human Body) (http://www.vesaliusfabrica.com/en/original-fabrica/the-art-of-the-fabrica/newly-digitized-1543-edition.html) in 1543, was considered to mark the foundation of European anatomy studies. Vesalius’ illustrations, like the lesser known Henry Vandyke Carter’s for Gray’s Anatomy, were produced in woodblocks for printing in ink. Vesalius’ figures resemble classical statuary. Many of his figures seem posed in dramaturgies of reflection and melancholy, sometimes holding their own flesh as if it were a cloak, around scenes of nature, or in chunks or ruins of architectural stone, as if contemplating their own death from outside their own body.

The word ‘fabric’ employed by Vesalius connotes ‘garment’, ‘structure’ and ‘craft or production’. I have heard people refer to their own body as a garment that can be shed at death. The idea of flesh as clothing is common. It is a one way to conceptualise a relationship between body and soul, the body irrelevant after death in fact. The idea of ‘craft or production’ suggests there is a concept of a creator to this complex form that is the human body. During the Renaissance period, anatomy was being performed in a society in which science and religion were deeply bound together. The word ‘fabric’ which connotes both cloth and the act of making something, thus signals also the Renaissance rationale that, in the transgressive act of going-where-only-God-should-go in cutting and dismembering the body, the science of anatomy reveals in the book of the body evidence of the perfection of the divine creator (See Jonathan Sawday). The Renaissance mind could not yet imagine a world order that was not God’s work.

Gray, rather than displaying the body in its entirety, focuses on the body parts, dispassionately and scientifically. His book was to educate the anatomist and student surgeon. The project grew out of Gray’s work in the Anatomy Workshops in Kinnerton Street, Belgravia, associated with St George’s Hospital in London where he worked.

The history of the book’s production and reception at the time is brilliantly told by Ruth Richardson in The Making of Mr Gray’s Anatomy, Bodies, Books, Fortune, Fame. The drama of this project’s development, the professional competitiveness, the relationship between Gray and his illustrator Carter, the technology of printing such a complex book at the time, all within the context of Victorian London culture and society, is vividly brought to life.

The current edition of Gray’s Anatomy reflects, of course, the contribution to anatomy that digital technologies afford. Its’ last 3 Editions have been published by Professor Susan Standring (see Interiority).

The body, a garment...

She says “I don’t need my body after death. Someone else can use it.” The body, a garment, like a second-hand suit hanging in a charity shop. Who did it once belong to? What was their name? Who did they love? How did they die? I think I want to donate my body. I don’t think of it as a garment. Because I don’t only think of its external appearance. But there’s the family to consider…

ANATOMICAL DISECTION

“The day we harvest the brain the anatomist gets each student to use the rotary saw across the top of the skull. A fine bone dust sprays. She hands it to me. I swallow hard, and work. The skull is thick as oak.”

Anatomical dissection needs a supply of dead bodies, known as cadavers in the medical environment. This isn’t something the average layperson necessarily thinks about. Perhaps we disavow the fact that medical training depends on the study of the human body and that, whilst digital cadavers and technologies are new methods for studying the human form in detail relying only on the eye, the traditional haptic hands-on method is still considered my many educators to be vital. This involves dismemberment and cutting through the human body, skin, muscle, nerve, organ, fascia and bone. Anatomical dissection is studied by medical students of all disciplines, as well alternative practitioners and some art students. Today, the provision of bodies is through voluntary donation, and the protocols around the handling of human material for anatomical study is respectful and highly controlled ethically.

The history of the provenance of human anatomical material in European medicine, however, is a grisly one. The nexus of crime and punishment and dissection is revealed throughout the history of the anatomists’ slab. Up until the 15th century, anatomists tended to work on the bodies of unclaimed cadavers. Then, in the 15th century when anatomy theatre became public and the demand for bodies increased, cadavers were recruited from executed criminals (Van Dijck). Subsequently, the dark culture of dissection in Europe moves from the criminal corpse to the destitute one, giving a clear and ongoing moral message the cadaver was the mortal remains of a person who was an outsider to society, possessing little value in life but immense instructive value at death.

In the Renaissance period, when anatomy and dissection become organised public, as well as professional, events, the provision of fresh human corpses was paramount. Without refrigeration, the body’s natural decomposition was rapid, which is why the guts and reproductive organs were habitually and logically the place to start. Hence the key message in Rembrandt’s iconic painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1632) in which it is the hand (that-did-the-crime) of the executed criminal-cadaver that is being dissected, leaving the rest of the body intact. This painting, designed for specific moral purpose, is far from a naturalistic depiction of an anatomy lesson at the time. It establishes unequivocally the authority of the anatomist over the dead body, as well as the double-penalty of capital punishment and posthumous corporeal humiliation.

Francis Barker on Rembrandt

The Rembrandt painting of The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp (analysed brilliantly by Francis Barker The Tremulous Private Body: Essays on Subjection) was the last image projected for the audience to think about in my 2007 production for Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, GlassBody: Reflecting on Becoming Transparent. The painting has haunted me since and perhaps provoked the need to explore the anatomy theatres of Renaissance Europe further.

The dismembering of the human body was a gruesome affair and one in which the dead body became an abject object. In England, anatomy was being performed in a society when brutal punishment of condemned criminals was performed in public – hangings, drawing and quartering and flaying – and a layperson would therefore easily associate the cadaver with a damned being, which they were considered, in fact. During the height of public anatomy, the criminal was doubly punished, by execution and by dissection. The journey from the scaffold to the slab was often instant, and there are accounts of bodies being dissected even before they are quite dead (Richardson). The Anatomy Theatre’s appetite for more and more cadavers developed an economy within the penal system itself. When there weren’t enough corpses available from the scaffold, the infamous practice of body-snatching from graves operated as an illegal underworld economy. Since women statistically performed criminal acts less frequently than men, the law had to shift so as to increase capital punishment for women and ensure a supply of female material (Richardson).

“Corpses were bought and sold, they were touted, priced, haggled over, negotiated for, discussed in terms of supply and demand, delivered, imported, exported, transported. Human bodies were compressed into boxes, packed in sawdust, packed in hay, trussed up in sacks, roped up like hams, sewn in canvas, packed in cases, casks, barrels, crates and hampers; salted, pickled or injected with preservative. […] Human bodies were dismembered and sold in pieces, or measured, and sold by the inch.” (Ruth Richardson Death, Dissection and the Destitute. p.72)

The trial of the famous body snatchers Burke and Hare in 1829, proved a deterrent to other practitioners of this form of theft, and this left the medical profession without anatomical material for some time. The government, lobbied by the medical profession, passed the Anatomy Act in 1832, permitting the legitimate purchase and acquisition of the corpses of lunatics and paupers. So now, if it wasn’t the condemned criminal providing flesh for the slab, it was the poor. If a dying person in a poor house or hospital wasn’t claimed at death by a family member within forty-eight hours, rather than the paupers grave, they would go straight to the anatomy lab. This created anxiety and rage among the destitute in 19th century London, who were largely defenceless, often illiterate and unable to leave written directions. In short, the destitute were utterly powerless in this flesh economy. And so, the Act, whilst wishing to end the barbarism of former times, did little in fact to make matters better for the poorest. (Richardson).

The 1832 law also produced corruption among those tasked with administrating the business side of selling corpses to the anatomy labs. Money was pocketed rather than put towards the workhouse budgets, whilst medics could profit by selling on body parts to other hospitals. The 1832 Anatomy Act regulations persisted, surprisingly, until the 20th Century, and a new act wasn’t passed in the UK until 1984, when The Anatomy Act repealed the 1832 Act so as to address the issue of transplants.

Human material can be big business...

Human material can be big business, even today. Today’s UK laws forbid any profit to be made from human gametes. Compare this, for example, to the profit-based economy of body parts in the USA. Paradoxically, the availability of human material in the USA due to its commercialisation makes it easier for people to obtain gametes in In-Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) protocols, simply because there is more supply of such – for those who can afford it. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) in the UK establishes the ethics of reproductive protocols to ensure that, by law, there is no profiteering https://www.hfea.gov.uk/.

THE VISIBLE HUMAN PROJECT

“Poverty and crime, coupled, as always. You didn’t even need to steal or kill. Just be wretched, without a bean for burial, and your body would be used as an object in the name of science.”

The morality play aspect of the Anatomy Theatre is chillingly restored in The Visible Human Project (VHP: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/visible/getting_data.html), the first complete digital database of the human cadaver to be used in the service of medical science. This was constructed from a male criminal in the USA, Joseph Paul Jernigan, who had been sentenced to death in 1993 and volunteered his body beforehand to be immortalised in this way. Although his identity originally remained anonymous, the Press in the USA got hold of the story and published many articles about the case, several commenting that in some way his posthumous donation to science was both a double punishment and a debt to society. Clearly the moral overtones of dissection-as-punishment still lurk in the public psyche. (Cartwright, Lisa, et al. The Visible Woman: Imaging Technologies, Gender, and Science. 1998. New York: New York University Press). The female cadaver on the other hand, was not sensationalised by the media as a punished criminal but known simply as a ‘housewife’. Her body was donated posthumously by her husband. Van Dijck comments not only on the criminal/layperson aspect of such narratives around these digitised corpses, but a gendered one: Jernigan, she writes, who was 39 years old at death, is considered ‘standard’ even though he had a missing testicle, whilst the woman (without name) is considered ‘imperfect’ since she is beyond reproductive age. It is interesting to compare this to the fact that Susini’s wax Venus, whilst not visibly pregnant, includes a foetus, as if celebrating her idealised womanhood as not only sleek, voluptuous, beautiful and yielding, but actively reproductive. “Significantly, the gender-specific criteria that we use to differentiate between living men and women are unilaterally projected onto these virtual cadavers” (Jose Van Dijck. ‘Digital Cadavers and Virtual Dissection,’ in Maaike Bleeker. Anatomy Live: Performance and the Operating Theatre. p.39).

Hollywood cinema and entering the body...

Hollywood cinema has expressed popular fascination with entering the body through technological science, using the idea of human miniaturisation in order to get inside. The 1966 science-fiction Cold War themed film The Fantastic Voyage presents the crew of a submarine mission shrunk so small that they can be injected into the blood system of a man suffering a brain clot. The moment they enter the body is magical, the body a kind of psychedelia, pulsing like a lava lamp, pink corpuscles floating by as the crew sail the treacherous path to the heart. The body is actually presented as a hostile environment. The conceit of scale distortion enables the conjuring of various threats to the mission, so that a sneeze might be the equivalent to a tsunami, whilst white corpuscles attacking the ship potentially annihilate it and all inside. The film, whilst promoting (Cold War) science at its most advanced, is perhaps subtly suggesting a creative intelligence at work in the continued awe and anxiety of the explorers into this complex and always dangerous environment, as they assert that “man is the centre of the universe.” Woody Allen in 1972 continued this idea of traveling inside the body with his satire, Everything You Wanted to Know About Sex. This sees Allen as an anthropomorphised spermatozoa, and a neurotically anxious one at that. He and his co-sperm are a kind of military operation going to attack the highly resistant and defended egg. Such cinematic depictions of the body’s interior evoke the stories of Jonathan Swift and Jules Verne, where human scale changes so that a familiar territory becomes transmuted into new and especially threatening forms.

BODY DONATION

“It’s how it should be. Vital to reunite the idea of a life, and a person, with a cadaver. To put all the pieces together again somehow in the mind. To re-member the dead. Respect.”

Today, bodies for anatomical dissection in the UK are donated. Donation schemes provide advice to the individual and their family about this highly sensitive process and protocols are strictly observed. In London, there is a very large and beautiful Annual Thanksgiving Service -complete with Kings College Choir singing – at Southwark Cathedral, for those ‘silent teachers’ who offer their remains to medical science in London.

During my research, I was introduced to the Donor Scheme at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland (TCD) (http://www.tcd.ie/medicine/anatomy/). This is run by two resourceful and compassionate Anatomy Technicians who have designed and preside over a particularly remarkable Donor scheme, Siobhan Ward and Philomena McAteer. I call them The Angels.

The two women work as counsellors and guides to those considering donation and to the families following bereavement. They accompany the donor throughout their journey from life to death. They have created special premises where they bring the donor’s coffin next to a small room where they provide – literally – tea and comfort at agreed anniversary or memorial moments during the donation period when relatives have to withstand the difficulty of not being able to perform a burial ritual. Burying the dead loved one is a recurring quest for those who cannot access the corpse. From Antigone to bereaved families of, for example, unrecovered plane crashes today, there is a strong human need to gather, bury and ritualise human remains. Different cultures do this in a range of ways, from fire to burial, to sky burial practice where corpses are left out in nature for carrion to feed on thus returning the body to the natural cycle.

What is also remarkable about the Angels’ jobs is that they also perform the role of introducing medical students to their first experience of working with a cadaver. Hence, they are dealing in a human, haptic way with the full cycle of life and death and the posthumous handling of the cadaver in protocols that they have carefully designed and administrate themselves. All donations are destined for the Trinity dissection labs. See a 2-part TV documentary about the work of the Dublin Donor Scheme A Parting Gift (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F7H_RmlPTnc). An Act of Remembrance is performed every two years, during the time the donor resides at TCD (http://www.tcd.ie/medicine/anatomy/).

In London, body donation is a city-wide project.

DECAPITATION AND DISMEMBERMENT

“My deepest terror is decapitation. Scares the shit out of me. (See how I just said ‘scared’ and ‘shit’ in the same breath? The human mind is the body. Any idea that they are distinct is not only dangerous but absurdly illogical.)”

This provokes a great deal of anxiety, but is the fact of the materiality of the anatomy lab. The body has to be taken apart to be parsed. There is surface anatomy and deep anatomy. For the layperson – and even for the student new to such – confronting dismembered body parts for the first time can be a shock. Flesh is harder to accept than bone somehow, perhaps because bones are such recurring cultural symbols, whereas the average member of the public will have seen far less depiction of severed and anatomised flesh. Bone is also durable and dry, whilst flesh decomposes, and as it does so produces an unbearable stench. At death, a decomposing body is abject material (see Kristeva). Great care is taken in anatomy labs to preserve body parts hygienically and prevent them from drying out so that they can be re-used. Those not working in the medical or forensic professions today are largely protected from the impact of death, and its aftermath, on the body. There is taboo around the corpse, with careful protocols around its presence, handling, and burial.

Our predecessors in Europe were far more used to the sight of the dead and mutilated body in a public arena. Our ancestors were also far more used to brutality, torture and abuse of fellow human beings, even in peacetime. Today there are parts of the world at war where such violence is a daily occurrence for civilians, and children are growing up brutalised by the sight of death and dismemberment. Even today there are countries, both at war and in peace, where brutal public executions – including beheadings – are performed in public, and by hand. It is in this context that we might understand the Guillotine as a benign killing machine, designed for both efficiency and speed of death:

During the Reign of Terror following the French Revolution there were 15,000 beheadings in the course of 9 months. The inventor of this razor-blade sharp and highly productive chopping machine, Dr Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, was in fact a humanist of the Enlightenment, committed to reform barbaric forms of capital punishment. Significantly, the speed of death at the Guillotine removed the spectacle of suffering – that had been seen previously as offering the possibility of spiritual redemption (Barbier, Laetitita. ‘Medusa and the Power of the Severed Head’. In ‘The Art of Dying’. In Joanna Ebenstein. Death, A Graveside Companion. 2017). Corporeal pain and mortification mimicked that of Christ on the Cross, enabling the idea of punishment and the quest for redemption.

The effect of instant dismemberment produced, in turn, ideas around a brief life-after-death in the victim’s head and face. It was said that heads bit, babbled and blushed. The latter arose when Charlotte Corday, who had assassinated the Jacobin leader Marat in his bath, was guillotined. It is said that her executioner lifted her head from the basket and slapped her face for the crowd’s entertainment in further punishment, and that she blushed. This provoked questions about consciousness-after-death and the relationship between body and soul: was a dismembered head still ‘feeling’? Furthermore, within the context of The French Revolutionary ideological world, the meaning of this purported event might have signified something more profound about a relationship between the self/body and the world at a time when religious belief was being re-evaluated. According to Outram “It is not surprising that the place, both where the displacement of religion was at its most visible, and where the question of bodily dignity was faced most painfully, should also be the place to produce a miracle located in the physical body” (Dorinda Outram. The Body and the French Revolution: Sex, Class and Political Culture. p.119).

One of the most remarkable aspects of the contemporary analogue anatomy lab, is that the medical student must encounter the cadaver in sections. They will be dissecting previously dismembered body parts that have been carefully preserved and are presented to them wrapped in plastic, sprayed with water (to prevent over-dehydration) on metal anatomy tables that have lids and controlled temperatures. In my experience at Kings College, initial awe by a young student at holding a severed head in her hands on her first day, soon gave way to relaxed comfort as acculturation set in.

The Anatomy Theatre in Padua...

In March 2018, I enter the Anatomy Theatre in Padua, the oldest surviving one, inaugurated in 1595. An icy shiver goes through my blood like a freezing electrical shock. I realise I am standing right where the slab would have been. I look up at the tightly packed wooden tiers of the amphitheatre that is tiny compared to its scale in my imagination from illustrations. It is uncannily intimate.

I notice huge candelabra and realise that this dark space would have been lit only by candles as there is no natural light at all. Dissections would take place here in February (same time as Carnival) when it was cold, so the bodies would decompose more slowly. Members of the public would buy tickets to watch, alongside medical students. I imagine the awe of this crowd of 200 people packed so closely together, hugger mugger, gazing down at a stinking cadaver as the Tutor named each part being parsed.

MEDUSA

“[Takes mirror and looks into it.]

Time to confront my own anxiety then. Time to look Medusa in the eye.”

Overarching any question of the impact and meaning of the severed head, is Medusa, the snake-headed Greek monster of mythology, who was beheaded by Perseus, as depicted so luridly in Caravaggio’s painting. Caravaggio’s Medusa is painted on a circular shield – a reflection – in which it was, according to Greek mythology, safe to gaze at her without being, literally, petrified. Caravaggio captures the way the myth of Medusa has been understood over centuries: a demonic monster-woman, a phallic-destroyer, presented on a reflective surface. Freud wrote that the Medusa myth is about fear of castration:

“The terror of Medusa is thus a terror of castration that is linked to the sight of something […] it occurs when a boy […] catches sight of the female genitals, probably those of an adult, surrounded by hair […] The hair upon Medusa’s head is frequently represented in works of art in the form of snakes, and these once again are derived from the castration complex. It is a remarkable fact that, however frightening they may be in themselves, they nevertheless serve actually as a mitigation of the horror, for they replace the penis, the absence of which is the cause of the horror” (Sigmund Freud. ‘Medusa’s Head (1922).p.202).

Sawday extends the idea of the anxiety of transgressive gaze to the entire body. He posits that the figure of Medusa (who appears in some anatomy theatre depictions) is appropriate to the danger of looking into the body’s interior, and the disquiet this provokes. He proposes that the idea of looking at the reflection of Medusa’s head in the shield evokes the idea of the taboo of our interiority, thus converting Freud’s castration complex into a broader idea of non-gendered angst regarding what we are made of, viscerally, under our skin, and prevailing ideologies concerning theology and the ‘right’ of science to enquire within:

“Modern medicine, for all its seeming ability to map and then to conquer the formerly hidden terrain of the interior landscape, in fact renders it visible only through scenes of representation. The more graphic the representation, however, the more the subject whose body is the object of scrutiny is compelled to look. In this, the search for the experience of interiority begins to appear as perhaps uncomfortably close to contemporary theorizations of the consumption of pornography” (Jonathan Sawday. The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture. p.11).

I note that the Medusa figure and her mythology might also have played its part – unconsciously – in the idea of Charlotte Corday’s life-after-death blushing: she was considered by the Revolutionaries a demonic woman. That she might have remained conscious for seconds after death suggests a dangerous tendency towards monstrous immortality that the Medusa head connoted.

Elizabeth Bronfen in her in-depth analysis of cultural ideas on death and femininity argues beyond and against Freud’s castration theory of the Medusa. She insists that the decapitation of the Medusa signifies a violence against feminine genitalia and connects this to her thesis that the woman’s corpse in the culture has been both an enduring aesthetic object and a source of terror for the onlooker.

“Like the fetish, this mythic figure (my reference is Medusa’s head) is ‘uncanny’ in that she frightens and reassures, in that she functions as both a site of lack and what covers the lack. Analogous to the way the sight of the corpse imbues the survivor with a sense of mastery over death, this spectacle of ‘sexual’ lack allows the viewer to isolate his own Otherness (the vulnerability of and split in the self), by translating it on to a sexually different body, and in so doing it works once again on the principle of an interchangeability between dead and feminine body.” (Elisabeth Bronfen. Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic. p.70)

Hélène Cixous, meanwhile, reclaims Medusa. Rather than the decapitated monster with snakes for hair who turns men to stone even after her death if they dare look her in the eye, Cixous’s Medusa laughs. This laugh is defiant and disruptive. In this text, that has become the foundation for écriture féminine (feminist writing) Cixous exhorts women to write herself from her body out of her oppression. It is precisely this access to women’s interiority that becomes charged with authenticity and revolt. To utter, to use language, is to insert oneself permanently into the world.

Caravaggio’s Medusa...

Seeing Caravaggio’s Medusa for the first time in-situ at the Uffizi in Florence was visceral: I walk past the entrance to the gallery and this blazing circle of green and gold light, like an eye burnishing in the distance, beckons you in. Though her face is larger than life-size, as an object she is quite small in fact. You could hold her in your arms. Her eyes seem to follow you in the room. She is painted on a shield that has the same convex shape as the lens of an eye. She is all eyes. Impossible not to stare at her.

THE ANATOMY THEATRE

“In the Renaissance, The Anatomy Theatre became a space not only for scientists but for popular infotainment. In Bologna, public dissection was part of carnival festivities: Sing! Dance! Feast! Turn the world upside down! Gawp at cut up human flesh!”

The goddess of division and dissection was a woman, Anatomia (from the Greek word for dissection anatomē) “whose attributes were the mirror and the knife. Those attributes were derived from the story of Perseus, the mythical hunter of Medusa. […] Medusa stands for fear of interiority; more often than not, a male fear of female interiority” (Sawday, p.3). Thus, the Anatomy Theatre’s purpose compresses two ideas, that of cutting into the body and the transgressive gaze of looking inside the body. The body had been opened up for dissection before the Renaissance. The European Anatomy Theatres of the Renaissance mark a cultural turn, however, playing their part in the scientific project of the day – that was in turn ideological – to organise knowledge systematically, through what Sawday calls ‘the culture of dissection’ and ‘divisionary procedures’ (Sawday, p.2). Not only did the Anatomy Theatres of Europe produce knowledge about the body, its structures, its parts, and its systems, but they offered this in what we would call today ‘public-understanding-of science’ arenas. Such spectacles are depicted in numerous artworks of the time, the most famous being that of Andreas Vesalius, whose work asserted ocular evidence and dissection and its interpretation, based closely on empirical observation. His revolutionary De Humani Corporis Fabrica (The Fabric of the Human Body http://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-20094, with its detailed illustrative anatomy plates, was published the same year as Nicholaus Copernicus’ equally ground breaking On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres (1543). Thus, the microcosm of human interiority moved on a pace at the same time as understanding of the macrocosm of astronomy was progressing; each demonstrating Man’s place in the universe, presided over by an almighty God. This idea is reflected in the organisation of La Specola in Florence, its collections from the body to astronomy arranged on different floors. Vesalius, for all his scientific advancements, maintained a close correlation between astronomy and anatomy, with a sustained conviction that the human body was evidence of divine design.

The European Anatomy Theatres and their Lessons were represented most potently by Dutch artists, whose luminous attention to detail in their canvases tell of a particular anatomical gaze at the time.

Rembrandt is perhaps the supreme master of such narratives, and his iconic painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1632) has been discussed already. What is striking in the Dutch paintings is the way on which the teacher-student-cadaver relationship is organised in a rhetorical choreography so that there is a conscious implication of the painter’s spectator in the dramaturgy and its meanings.

Above: The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Cornelius Isaacz’s Gravenzade (1681)

Whilst there is no evidence that Shakespeare attended the Anatomy Theatre at the Barber Surgeons Hall, just minutes’ walk away from the Globe Theatre in London, Sawday muses that a civic dignitary might have been invited to attend an anatomical dissection whilst Hamlet was playing around the corner. He thus makes a connection between anatomising and soliloquy. Sawday notes that Shakespeare’s language, as with other poets and writers of his age, engages with the idea of ‘autopsy’ (seeing within oneself) “We watch and listen, as Hamlet sets about the dissection of both himself and the gangrenous body-politic in which he is enmeshed, deploying the scalpel of an emerging language of self-reflection” (Sawday, p.38). Soliloquy, autopsy, dissection, then, each serving to advance human knowledge on the path towards 20th century existential human, but passing through several phases of theological rationalisation before entering the truly modern period of enlightened scientific detachment from the body on the dissecting table, and the idea that, without Divine Creation making sense of the world for us, we must take responsibility for it. Sawday’s ideas on the exploration of human interiority stimulated my Athletes of the Heart project of interdisciplinary talks Interiority: An Exploration of the Inward Gaze.

THE DISSECTION LAB:

CONTEMPORARY PUBLIC ANATOMY

“The students unwrap their specimens. Flesh drained of blood is leathery. A young woman with bright red hair is holding an old man’s head in her hands. Gazing at him, transfixed. I ask her what she’s thinking.”

If the Anatomist was dignified with the authority of objective knowledge, a master of ceremonies in theatres of cruelty in which knowledge of human corporeality and their place in the world was, literally, laid bare, he (invariably it was a He though there was an Italian woman anatomist in the 14th century, Alessandra Giliani, and several women in 18th century Europe) was a showman. The Anatomist as entertainer in a mass spectacle is reinvented in the, perhaps consciously contrived, eccentric figure of Gunter Von Hagens. Using a technique of plastination, Von Hagens preserves (donated) bodies and arranges them in any number of theatrical poses. There are footballers kicking, a horse rider and horse, and a pregnant woman reclining, her arm above her head as if inviting the spectator in to her womb. Von Hagens has sliced the body into fine millimetre cross sections, isolated blood systems to show the structure, and much else besides. He is an entertainer, his global industry Body Worlds attracting queues of those with morbid fascination, or just simple fascination, with the sanitised spectacle of human flesh in all the guises that he offers. In Von Hagens’ four-part Channel 4 documentary Anatomy for Beginners (https://youtu.be/kbyUzsHP3Po) we have him presenting his constructed couple “breathless, melodramatic and just a bit salacious” (Maxwell, Ian. ‘‘Who Were You?’: The Visible and the Visceral,’ in Bleeker, p.51). Whilst one might be critical of his narcissistic presence in his exhibitions and his broadcasts, in fact, as Maxwell also suggests, “What might be dismissed as mere populism is reframed as the very acme of the enlightenment project: the democratisation of knowledge […] For Von Hagens, visibility is inherently democratic; more, visibility is itself conflated with an aesthetics idealism: the transcendent beauty that he is able to reveal for everyone constitutes the justification for his work”(ibid., p.54).

Von Hagens...

You can’t ignore Von Hagens. Perhaps, like Marie Tussaud in her day, he is appealing to our deepest anxieties as well as curiosity and desire to gaze safely at what terrifies us: dangerous criminals and/or our interiority itself. I found his exhibition both exhilarating and provocative. That he can reveal so much and so clearly it is a gift to public knowledge. That he ensures that he as the creator is always present is very disturbing. Why do we have to keep knowing he’s there? It is as if he wants to be the protagonist of his very own theatre of death and preserve a God-like status over the domain of his plastinated corpses.

But then, perhaps he is no different than his predecessors in the historical anatomy theatres of Europe. Here too the anatomist is a Master of Ceremonies, endowed with both authority and charisma. For, knowing the body in such detail, being able to touch it, display it, animate it (as Von Hagens does in his TV lectures in order to demonstrate a joint, for example), and bring this to our consciousness, is an extremely powerful act of transmitting knowledge. That Von Hagens uses the media and profits from his spectacular bodies is both contentious and unremarkable in the history of anatomy and its exploitation of dead human material.

METAPHORS OF THE HUMAN BODY

“Each body opened will tell a different story, of a life lived, of a death – perhaps how. A blackened lung. A swollen brain. A piece of metal holding two joints together. I’ve seen this. It’s all there, inside, the skin the container of it all.”

For Western minds, the human body has conjured many metaphors, that can in turn signal cultural attitudes. The body has historically been compared to a book, a text, a landscape, a territory, a container, a vessel, a temple, a house. Thus, it has been conceived as material to read and interpret, as a domain over which to have mastery and a terrain to colonise, and a designed space in which the complexity of the interior is marvellously organised into structures and systems. Even to a contemporary, secular, eye, the sight of the body’s interior has led to a sense of wonder at its remarkable complex and efficient design: “The argument from design has long been discredited, but its seductive attractions are evident when you look inside the human body. Everything seems so lovingly packaged and arranged, like a cabin trunk stowed against breakage with just those items necessary for the voyage” (Dibdin, Michael, Chapter 1 ‘The Autoptic Vision’ in Sawday, p.6).

It is hard not to feel somehow that the scientific theory of evolution has some poetry to it. The body itself constitutes a highly complex set of structures and systems that work internally as a kind of interdisciplinary dialogue, and in turn ensure the greatest protection for itself from outside threat. The skin, that enormous organ that protects us from the elements, the brain that is carefully nestled into a very thick bone crash helmet of a skull, or our precious heart and lungs protected by the strong structure of rib-cage, each provoke awe at their intricate efficiency. We are, as a recent advertisement proclaimed “amazing”. Cutting open the human body to discover what it is made of, how it works, and how it moves has been an enduring, compelling, endeavour across the ages.

The Western mind has of course constructed ideas about the human body according to prevailing ideology. The concept of the body for the Chinese, for example, is quite different from ours. The body is perceived as an entire and holistic system, picturised quite differently than early anatomical images of the same period. Shigehisa Kuriyama opens his extraordinary cultural history of medicine with the striking evidence that, whilst the ancient Greeks idealised the human form as muscular – and so muscles are distinguished from the rest of the body parts – a Chinese drawing shows only an outline of the human form “Muscularity was a peculiarly Western preoccupation” (Shigehisa Kuriyama. The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine. p.8). His other comparisons that demonstrate utterly divergent concepts of human anatomy, he argues so persuasively, are the result of cultural looking (“my thesis is that the history of conceptions of the human body must be understood in conjunction with a history of conceptions of communication” (ibid., p.107). Kuriyama also discusses vital knowledge such as of the pulses: the several in ancient Chinese medicine as still used in Acupuncture and Chinese medical practices today, as compared to the one pulse that the contemporary Western doctor will feel. If a doctor is asking only one question of the pulse – heartrate – then there is only one pulse to feel. By contrast, the Chinese system understands the body as a complex set of relationships, with several pulses giving different kinds of readings of these. Furthermore, he stresses the importance of language in what he calls ‘styles of seeing’:

“[in Chinese medicine, where touch is used for diagnosis] Qualities thus defined themselves and each other, clustering closely, and differing by fine, gossamer veils of sensation, subtle shades of faintness, weakness, softness. No trace here of crisp, categories such as size, speed, rhythm, and frequency – the geometrical logic of space, time and number […] In the porousness of the intercourse among words, we couldn’t be further from the sharp demarcations that European doctors thought necessary to secure science” (ibid., p.94-5).

In short, knowledge – even knowledge of the convolutions of the human body, how to read these and cure ailments, is framed by ideology. There is no absolute Human Anatomy, only the evidence of its materiality, its structures and its (culturally-specific) naming; and that it can be comprehended, only and precisely, according to the ideologically informed gaze upon it that in turn conditions those questions being asked of it.

Western view of medicine...

My work Anna Furse Performs an Anatomy Act: A Show and Tell is absolutely rooted in the Western traditions of anatomy. This is not because I subscribe to the Western view of medicine only. I use complementary medicine far more than traditional pharma on a regular basis. I know acupuncture works for me. However, there is far more tension, contradiction and compelling drama to explore in addressing the European roots of anatomy. In my performance, I don’t even address alternatives. There is only so much you can do in an hour.

WAX

“In a nutshell, what Descartes was saying is because wax is mutable, yet we still recognise it as wax, it is the mind that we must trust, not our senses, in seeking truth. Before him, the human body was a sacred land. After him, a machine. We think. We are.”

Wax has been a significant material for many cultures. The bee is a symbol of wisdom in the Christian Church, signifying the transformation of labour into goodness and within a society that operates to a clear hierarchy. The labour of bees is pure, as are the fruits of its labour – wax being considered the fruit of a virgin effort and thus deserving of its place on the altar, as in church candles. The other product of bees is of course honey, used for both medicinal purposes and as a food in many cultures, even today. The ancient Egyptians were avid bee keepers, using wax for many things including, as a depilatory (as still used today) and, mixed with resin, for writing as well as for sculpture. Wax has of course been used as a source of light for centuries. The stuff – lustrous, fragrant, delicious, healing, light-giving, both beautiful and practical – also suggests transience (Descartes).

For creating sculpture, wax came into prominence in Europe in the 18th century Enlightenment. As a material for representing the human body, mixed with pigments, it was ideal: malleable, and, when hardened, appearing soft and moist, resembling flesh. The most famous wax artiste is of course Marie Tussaud, who first came to London to exhibit her works after the French Revolution (whom she had served with her waxes as she had served the monarchy in Versailles as an art tutor prior to 1979). Travelling to Scotland, Ireland, in several English cities with her exhibits, she eventually stayed in London and set up her own permanent exhibition. Using real human hair, glass eyes, and with a meticulous sense of realism and representation, Tussaud’s work was as brilliant as her life was remarkable for a woman of her time. Here is another criss-cross of themes involving wax, anatomy and crime:

“Additions were made [to her travelling exhibitions] as notorious crimes occurred. Among the biggest crowd-pullers were the portraits of Burke and Hare, the body-snatchers […] the trial and conviction of Burke provided her with an opportunity to catch the public interest.

On Friday 13th February [1828] she made her announcement:

NEW ADDITION

BURKE THE MURDERER

[…] It represents him as he appeared at his trial and the greatest attention has been paid to give as good an idea as possible of his personal appearance”

(Pauline Chapman. Madame Tussaud in England, Career Woman Extraordinary. p.53)

Wax and Descartes’ thinking...

In 1994, I directed a play by Lavinia Murray, Wax: The Secret Life of Marie Tussaud Waxwork Artiste Extraordinaire and Witness to the French Revolution (http://painesplough.com/play/wax). The Descartes puppet, made by Agnes Treplin, from this show found its way into An Anatomy Act. Impossible to resist using him and quoting him here. The link between the material of wax and Descartes’ thinking as referred to by Lavinia, in my piece resonates with the wax models, not of Revolutionary France, but those astoundingly beguiling and frankly visceral anatomical waxes of the same period made in another country for another purpose. There is no doubt, however, that wax as a material for sculpting human flesh manages to captivate the imagination then, as now. Marie Tussaud in London has become a crowded theme park and top-of-the-list of tourist attractions, and remains a site of fascination. Wax representations of well-known human beings are extremely atmospheric. Some of them can be so lifelike that you expect them to breathe. Different from marble, bronze, or stone, wax itself appears so very realistic even though it is so very different from flesh to touch. Wax is the perfect material for the illusion of flesh.

ANATOMICAL WAXES

“She’s like a pie or a pot, with a lid that you can open, and literally take apart her insides like a puzzle.”

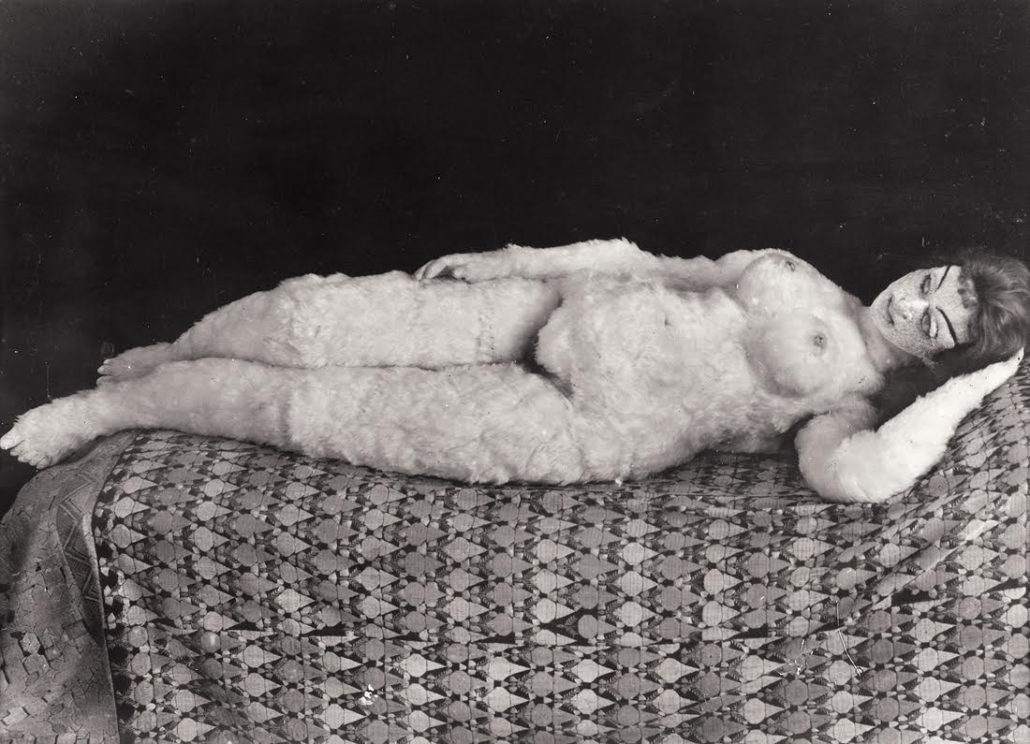

There were different techniques for such wax modelling. Some were mixed with other materials. Some were sculpted onto real bones. Some were made from plaster casts of original organs. This produced not only a range of anatomical themes, but different styles. For, as you look with your own eyes more closely at the anatomical waxes and their fabrication processes, scale and presentation, you come to realise how each wax maker was in fact an artist, interpreting as well as representing reality. Added to this, you also realise that even an apparently life-like human representation of the human form in wax, was actually created painstakingly over time by observing scores of cadavers, as wax making took time and cadavers would rot fast without refrigeration. According to the guide at La Specola (Observatory) Museum in Florence, some waxes used 200 cadavers in their creation. Thus, a single wax model is in fact an assemblage: she is created from observing many cadavers, chosen to resemble each other as closely as possible in age and size. In Florence, some of the most startling anatomical waxes were created by the brilliant Clemente Susini (1754 – 1814). Susini produced the Venerina, (Anatomical Venus) – or ‘slashed beauties’ as they were called – a series of similar supine figures. The fact that the models were made from observing many cadavers is a vital point to grasp when considering how ‘life-like’ the Anatomical Venus and her sisters appear to be. These figures were made of wax, with real human hair. The Anatomical Venus’s faces were sculpted and face is the same (c.f. Barbie dolls). The figures have a lid that can be removed, like a pie or a pot (from the Production Anna Furse Performs an Anatomy Act, A Show and Tell). All their parts can be taken out, like a virtual dissection. Inside this figure is a small foetus, although she doesn’t appear pregnant on the outside. This is signficant. For the Venere is an idealised representation of feminine beauty and function. Susini acknowledged that in his male waxes he was paying tribute to Michelangelo (the gestures are identical), whilst the Venus’ yielding attitude in her upper body evokes strongly the St Theresa of the sculptor Bernini: head back, eyes half closed, lips parted. The Venus and her sisters lie in attitudes of voluptuous ecstasy, lithe, naked but bejewelled with pearl necklaces (also made of wax). She is portrayed as if she has abandoned herself to death, orgasmic as a saint, offering the spectator the thrill of entering her (sic) and opening her up. She lies on a bed with sheets and a pinkish mauve satin mattress. At first this evokes a bed, evoking eroticism. In fact, this detail connotes the Catholic sacrament, the colours and fabrics worn by the priest and fabrics found draping the altar. Furthermore, the positioning of the figure on this bed evokes that of Christ as placed traditionally – and even today – in Churches during Passion Week in Italian Easter celebrations. Thus, we must understand Susini’s wax works on female anatomy not only in their scientific, but also in their cultural, meaning and significance.

The Anatomical Venus was on the itinerary of the European Grand Tour, the study of classical art and culture in Greece and Italy enjoyed by young aristocrats as a kind of finishing school of intellectual sophistication. There can be little doubt that these figures, whilst made with scientific intention, are in fact cultural creations, a form of anatomical pornography inviting a particularly intrusive, salacious and prurient gaze.

DOLLS

“Some men like playing with dolls.”

In her chapter ‘Ecstasy, Fetishism and Doll Worship’ (Joanna Ebenstein. The Anatomical Venus: Wax, God, Death & the Ecstatic.) Ebenstein introduces the compelling story of the painter Oskar Kokoschka’s obsession with his former lover Alma Mahler, widow of the composer Gustav Mahler. Alma was a celebrated muse to creative men, hotly pursued and alluring. Seven years Kokoschka’s senior, one of her main attributes was clearly hard for him to accept: she remained fiercely independent.

When Kokoschka was fighting in WW1, Mahler married Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus school. Kokoschka, unable to come to terms with losing Alma, commissioned a life-size doll of his beloved from the toy maker Hermione Moos. Wanting her to have a mouth that opened and teeth (perhaps so as to engage in sexual acts with this effigy?) the doll eventually arrived covered in fur, life-sized, but hardly a realistic representation. Perhaps part art-project, Kokoschka nonetheless painted her many times and also took his life-sized Alma toy out with him in public, to restaurants and parties. “Eventually, Kokoschka’s doll was ceremoniously doused in red wine and beheaded at a party” (ibid., p.195). This story of course wove its way into the performance, since the intersection of Mahler’s surviving widow with the continuation of the Anatomical Venus life-size doll trope and its beheading put a pin through the themes of Mahler’s music, women’s bodies as objects of gaze and possession, and the troubling idea of dismemberment as punishment.

Dolls and anatomy...

It is a well-known fact that the Barbie doll has body proportions that, if translated to human scale, would create impossible bodies that would not be able to function or move. The idealisation of Barbie as a girl doll (as well as Ken as a boy doll – neither of whom have genitals) has been an enduring way to mis-educate children since she was first created by the Mattel company in 1959. Efforts to create alternative types of doll include my favourite from the 1990s (made from a cottage industry in Australia, now no longer available) the Ruby doll. She had curves as well as pubic hair. I wrote about these toys in my play on eating and body-image disorders Gorgeous for Theatre Centre (Theatre Centre Plays, Volume 2. p.137-162). As for life-size dolls that grown men like to play with, there are plenty online with whom they can have sex. Even Amazon boasts “realistic life size sex doll for men with vagina and big breast” (https://www.amazon.com/Realistic-life-size-vaginabreast/dp/B005EXHX5I). In an age where, despite gender equality being far from achieved, but nonetheless where money can be made from notions of level playing fields, we can find products of all kinds, life-size dolls are no longer the prerogative of heterosexual men. The Independent reported in 2015 that “male sex dolls are officially on the market”) (https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/terrifyingly-lifelike-malesex-dolls-are-now-on-the-market-but-surely-women-wont-buy-them-10410553.html). But let’s not confuse dolls with anatomy, whilst noting that historically the two have in fact overlapped in a range of sometimes eerie, morbid and fetishistic manifestations. (See Ebenstein’s Anatomical Venus and Morbid Anatomy).

THE BLASON:

WRITING (ON) THE BODY

“Elizabeth 1st, the Virgin Queen, did a really extraordinary thing. She appropriated the blazon. In an explicit act of self-blazonry, she would expose her upper body, breasts and belly to her courtiers and visitors. She was quoting the poetic trend, she was quoting the anatomy theatres, she was revealing to those around what was denied to them in reality: her body. She was metaphorically performing an autopsy, taking control of the body-politic through her own revealed, virgin, untouchable flesh”

The idea of the body as a text, as a grammar and as a stimulus for writing is a well-traversed path in literatures across the ages. Feminists have grappled with the relationship between the body and language in a phallocentric culture. H.l.ne Cixous, in her The Laugh of the Medusa (1976) proposed the idea of L’écriture feminine: that since ‘woman’ is supposedly decentered, defined by a lack of phallus (Freud), then she is paradoxically free from the (patriarchal) rational order, and can use her ascribed irrationality – this “dark continent” (Freud) – of her body to write from. Feminist cultural and literary theory, recurrently embroiled with negotiating Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis, has continued to debate what constitutes womens’ alterity, and how we might understand the affect of gender on language, expression, speech and the imagination. The idea of writing the body, and from the body, has produced, in turn, the idea of writing on the body, a turn of phrase in English that provides a neat punning device. For, whether in the context of discussing hysterias, and how here the body ‘writes’ a semaphore of symptoms with no organic base on the body of the sufferer as an abreaction to trauma (sexual and/or violent), or whether discussing the (woman’s) body as a topic, the idea that the body is inscribed with meaning is a powerful one, and that can be applied to a range of identity issues and experiences of the marginalised. The body itself is a sign-system then. The body and its cultural history – and the woman’s body as Othered in a phallocentric culture – is understood as another kind of book that sits alongside the medical-anatomical. And this book shifts according to time and place.

However, Jonathan Sawday introduces another fascinating dimension to the body being written from and on: it is the body written about in a specific, parsing way. His thesis stresses the interface between the idea of the body culturally and anatomically in the Renaissance period, and he tells of a poetic form that bridges both:

“The blazon as a poetic form – usually understood as a richly ornate and mannered evocation of idealized female beauty rendered into its constituent parts – may seem worlds apart from the corporeality of an anatomy theatre. But, as we have already seen, the anatomy theatres themselves were decked out with all the ornate trappings of what we might call a corporeal aesthetic” (The Body Emblazoned, p.191).

The vogue for writing blazons, that coincided with what he calls the ‘Vesalian Period ‘(ibid., p.192), he argues, effectively reflected “a new, scopic regime of division and partition” (ibid). This gaze fetishised womens bodies, breaking them down into the smallest features that might be eulogised – eyebrows, breasts, eyes – by male poets. Then, the Court, so deeply associated with anatomy theatre through the idea of the chain of being, that meant the monarch held power, not only of the nation’s health but over individual bodies, had a Queen who reigned with a startlingly erotic dramaturgy.

Elizabeth 1st, the Virgin Queen, appropriated the Blazon:

“The Queen’s natural body was presented to her surrounding courtiers (by Elizabeth herself) in a fetishistic display. Bare-breasted, as were all her ladies at court prior to marriage (an event for which her permission was required), the queen circulated among her subjects […] It was she who, metaphorically, held the knife to her own body” (ibid., p.198).

In this way, Elizabeth commanded that her body be both revealed and denied to her courtiers, who must in turn celebrate her corporeality.

THE HEART

“Our hearts don’t disgust us. They’re cute. The heart is a logo. A sign for a feeling.”

Our idea about our body parts is, in Western culture, extremely hierarchical. Whilst we might argue that in a post-Cartesian sense, the Mind (brain) has taken priority over everything else that constitutes being human, the heart has in turn occupied an enduringly special place in ours and other cultures. Perhaps because the heart beating in response to experience, faster and harder when exerting, or in states of high emotion, it would seem that the human heart has been known about, and picturised in endless forms and contexts. Where Galen was doing anatomy on pigs and finding out about their hearts in Rome in the 3rd century, by the Renaissance, when the anatomists were opening the human body to find this vital part, knowledge about the heart began to advance. The Englishman William Harvey, educated at the University of Padua (where Galileo famously taught between 1592–1610) published his theory on the circulation of the blood in 1628 in a book On the Motion of the Heart and Blood (1993. New York: Prometheus Books).

This was a revolutionary discovery that was to change the course of Western medicine.

The heart meanwhile, has come to signify Christianity (the sacred heart) and love, the Festival of St Valentine’s day flooding the market with all manner of heart kitsch. Meanwhile, in music, poetry, painting and performance, the heart continues to occupy a central place in our imagination. There are many verbs for what happens to our hearts emotionally – they can soar as well as stop – whilst the idea of dying of a broken heart has come to be thought of as probably, in fact, from cardiac failure, since intense shock and emotion can contribute to heart stopping stress.

Louisa Young, meeting the surgeon who had been operating on her father’s heart, and realising that this hand had touched his heart, has written a wonderful cultural compendium The Book of the Heart: “I looked at his hand. I couldn’t touch it. That hand had touched my father’s heart. Mended it, to be sure, and saved his life – but touched it. […] It seemed disrespectful – a little heretical”. It is a volume that apparently defies categorisation, which is why when it was first published and I sought a copy around Valentine’s Day, Waterstones didn’t have it on their shelves nor could trace its whereabouts!

What interests me is how we love the heart so dearly that we have converted into a sign as well as a symbol, whilst there are equally important body parts, such as the lungs or liver, for which we not only do not have a clear mental picture, but which lack any visible evidence in the popular culture. Again, like the distinction we make between a disgust for flesh that putrefies and an acceptance of bone – a natural material that humans have even made ornaments and jewellery from – the heart, as I state in my performance, is considered a far superior body part to send to a loved one on 14th February than, say, an anus.